The Radical Imagination of Frantz Fanon

Fanon’s vision of a world freed from the shackles of racism can still influence our personal and political lives.

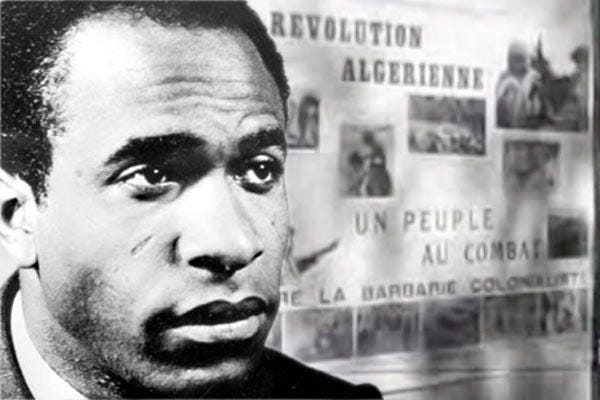

To read the words of a revolutionary is to be inspired for a better future. That’s how it felt when I first encountered Frantz Fanon. Born on 20th July 1925, the French West Indian psychiatrist and political philosopher has had an enormous influence in the fields of post-colonial studies and critical race theory. He’s also had an equally profound effect on my personal life.

Eighteen is an odd age because it is pregnant with possibility. It’s the age when we start fumbling towards a sense of who we want to be; a journey punctuated with occasionally discovering who we really are along the way. As a fresher, I quickly became adept at projecting the certainty of adulthood whilst quietly blinking away the shy precociousness of inexperience like so many of my peers.

To grow up in the United Kingdom as a young immigrant with a funny sounding name and an even (at least until I was 16) funnier accent is to experience instances of overt discrimination. Beneath the anecdotal, however, lies a fathomless abyss of structural racism; a system whose contours I could barely make out, but whose dimensions were increasingly thrust into focus with every attack.

Much of my time as a history undergraduate was spent observing the outer world of the past. But I was frustrated at my inability to articulate the wider picture of the racism I experienced; where had it come from? How has it adapted? How can you defeat it?

Then I read Fanon. And a clear bell rang in my mind.

Fanon’s Black Skins, White Masks was presented to me in as innocuous a manner as possible. The book was part of an optional module’s reading list. I knew nothing about him, save that he was the only person of colour on said list, and that his book (the term seems so limited given what it really is — part polemic, part psychological study, part clarion call for resistance) prompted the lecturer to warn me that Fanon “…can be a bit angry.”

This is code. Everyone who has experienced racism implicitly understands it. Whenever men or women of colour (especially Black or subaltern) dare to write about their experiences, or challenge the systems that deny them dignity, they are branded “angry” by the dominant majority. Fanon is angry, yes. But it was something much more glorious than my own pedestrian anger– it was the fury of resistance. Of defiance. And, critically, of hope.

As a psychiatrist liberated from the need to pretend colonialism was something laudable by virtue of his Blackness, Fanon was in a unique position. He was able to elucidate the “epidermalization” of the inferiority that is drilled into the psyche of the native by the violence of the settler.[1] It was thrilling. My course dealt with the external reality of colonialism — but Fanon spoke about the internal mechanisms with a stunning frankness. The function of racism was to make sense of the senseless violence at the heart of colonialism that robbed the dignity of spirit based on the colour of flesh.

Fanon’s masterful analysis of the historical function of colonial racism — “a systematic negation of the other person and a furious determination to deny the other person all attributes of humanity” helped me put my own personal experiences over identity into context.[2] For the first time in my life I had a starting point to examine my own uncomfortably malleable and distressingly unrooted sense of self. His observation on the psyche of Black men returning from the metropole “speaking correctly” as “aspiring to whiteness” in particular brought up uncomfortable memories of wanting to desperately speak like a white man to escape mockery, only to have the surreal experience of second-generation kids insulting me for sounding like an Englishman [3]. As Baldwin observed decades after Fanon, how one speaks not only reveals the speaker but defines the Other.

In time other names began to populate my worldview and nudged me towards an understanding of post-colonial racism and structural inequality beyond the UK. Stuart Hall. Claudia Jones. Ambalavaner Sivanandan. BR Ambedkar. Malcolm X. Edward Said. But it was Fanon that lit the match.

Reading Fanon teaches you that opposing systematic inequality is an all-or-nothing proposition. You can’t pick and choose #BlackLivesMatter but ignore anti-Semitism for example. Neither can you elide over the historical anti-black attitudes in your own communities by virtue of being a Person of Colour, or deny the voices of those oppressed by them (which, back in India, means Dalit, Adivasi, Muslim, and Kashmiri lives). To experience structural inequality whilst refusing to acknowledge your own privilege and perpetuate other inequities is hypocrisy of the worst kind; born of appropriation rather than critical reflection.

There are conversations surrounding race, and empire, and identity that I never thought would happen in the UK and the West. I am not naïve enough to believe things will change without a fight — or that this is a process that, frankly, Europe and its enfant terrible the United States will actually engage in. But I do believe it can be done; a hope nurtured by Fanon’s own exhortations.

I understand now why people misunderstand Fanon and those like him who seek decolonisation. Edward Said once said that the purpose of his work was to break down the Eurocentric idea of “insular” or “exceptional” civilisations; not to establish a different form of exclusivity, but to establish an accurate picture of our interconnected histories.

It’s a sentiment that Fanon would approve of. He refused to dedicate himself to just reviving a “black civilization unjustly ignored,” but rather fought for a dream of advancing humanity through dignity for all.[4] “If we want to bring it [humanity] up to a different level than that which Europe has shown it, then we must invent and we must make discoveries,” was his conclusion.[5]

It frightened and agitated those invested in maintaining their whiteness; the same type of people who now feel compelled to respond to #BlackLivesMatter with the flaccidly bigoted “All Lives Matter”. Fanon’s conceptions of violence are rooted in a specific colonial context, but an argument can be made that the “violence” of taking down statues of enslavers, rapists, and imperialists plays a similarly cathartic “cleansing force” as taking up arms against the oppressor.

To read the words of a revolutionary like Fanon is to be inspired for a better future. It is to take up the banner of the glorious cause he espoused — a vision of a world freed from the violent shackles of racism.

And, to paraphrase him, it is to find solidarity with every act that has brought victory to the dignity of the spirit.

[1] Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (New York, 2008 [1952]), p. xv.

[2] Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (London, 2001 [1961]), p. 200.

[3] Fanon, Masks, (p. 19).

[4] Ibid, (p. 201).

[5] Fanon, Wretched, (p. 254).